In the beginning stages of my chronic illness journey, my internal Dismissal of the seriousness of my condition was validated by External Dismissal from the medical professionals from whom I sought help. But the dismissal spell broke when I found myself in the ER for the eighth time, and my mom called and demanded to be put on speakerphone to talk to the doctor.

“Jayne has been in and out of the ER for weeks now,” she said. “She has a habit of downplaying her symptoms, and because she is young and ‘looks good’ doctors dismiss her all the time. I am a nurse, I know something is wrong here, and I will not let my daughter leave the hospital tonight. I am worried about meningitis. Do your due diligence!”

The doctor replied, “I mean, I’m always excited to do procedures, and I’d be happy to do a spinal tap to test for meningitis. But I don’t think your daughter has that, ma’am. I think she just injured her neck.”

I felt myself cringe. Why did my mom have to make a fuss? But I was also angry: Who the fuck did this doctor think he was? I hadn’t injured my neck. He didn’t know anything about me! Meanwhile, the pressure in my head was so intense, it felt like my eyes were being pushed out of my skull from the inside, like a gruesome scene from Game of Thrones. I was achy like I had the flu, and all I wanted was for it all to just stop. I felt like I was dying. In hindsight, I wasn’t far off.

Before I knew it, the doctor had snapped on a pair of rubber gloves, assembled his set of shiny, cold, pokey-looking tools, and was asking me to bend over so he could sterilize the area on my back where the needle would be inserted. I was shocked that we were going to do a spinal tap right here in our ER room. As I looked around, I saw a ball of human hair rolling on the ground like a tumbleweed. My gut clenched; this all felt too casual. Wasn’t a spinal tap kind of a big deal? But what did I know? I was the patient, and he was the expert, so I didn’t say anything.

The doctor was acting so blasé about it all, but it turns out he forgot one very important part: to measure the opening pressure of my spinal cord where my cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) was released. This measurement would have shown an increase in CSF, a small but significant detail that would prove incredibly important later on.

When he finished, the doctor said, “All right, I’ve patched you up. I’ll get that tested for you. Just wait here.”

Miraculously, as my fiancé Sean and I waited for the results, I started to feel better. The color came back to my face. I could form sentences, and I was even laughing at Sean’s jokes. And when the doctor returned, there it was again: External Dismissal. In a smug tone, he said, “Your tests came back normal.”

I was utterly confused, feeling both disappointed and relieved. I just couldn’t shake how quickly he was dismissing my pain—and yet how excited he’d been to “experiment” on me. But I was feeling better, so maybe it had all been in my head. I was sent home with some Valium, eager to get back to life as “normal.” And there it was again: my own Dismissal of my body’s wise intuition.

The next day, I saw clients and resumed my usual workout routine. I even went swimming in the pool that weekend (nobody told me you’re supposed to wait six to eight weeks before swimming after a spinal tap). “See, I’m fine!” I told myself. But five days later I couldn’t see. Walking was a struggle as my balance was off-kilter, and my pain was at an eight out of ten. By the time I ended up in the ER again, I felt like I was going crazy.

But this time my mom was in town, and she was loud enough and advocated hard enough for me that the hospital brought in the neurosurgery team. I was immediately admitted to the hospital, where I was told that I most likely had a brain tumor, sent up for an MRI, and given another spinal tap, this time checking the opening pressure. The results showed that I did not have a brain tumor and was in fact experiencing pseudotumor cerebri, also known as intracranial hypertension. The excess CS this creates causes pain, loss of sight, nausea, vomiting, loss of balance, and ringing in the ears, among other symptoms I was experiencing. The reason I felt better after the initial spinal tap was that the excess fluid being drained had relieved the pressure on my brain.

When I finally received my diagnosis, I felt both stunned and validated. All of my symptoms and pain had been real all along, but my own Internal Dismissal had been validated by the doctors’ External Dismissal. Like so many of us, I had been silenced, and therefore I continued to silence myself.

Perceived Body Betrayal

My wedding day did not turn out how I’d always pictured it. Both of my parents held me up by my spray-tanned arms as I carefully made my way down the boardwalk aisle and onto the sandy beach, where Sean, and our wedding party were all masked up for our COVID ceremony. Not only did I want both of my parents by my side for emotional support, I needed them for literal support.

In the months prior, I had undergone some of my most serious surgeries to date and begun using a rollator mobility aid. It was the exact same model my ninety-eight-year-old grandmother used. She called it “the Cadillac of walkers,” but it felt anything but sporty to me. My body was also bigger than the ones society had told me I must emulate to be the perfect bride: a single-digit size, with perfectly toned arms; a flat tummy; no scars, cellulite, or stretch marks to be seen—and certainly no neck brace! I’d put on a brave face, but if I’m being honest, I was petrified. As a newly disabled bride, not one of the Pinterest boards I’d created or looked at reflected my experience. None. Zero. I had no choice but to just do it my way.

Arriving at the rustic driftwood altar, I saw everyone swaying to the Beach Boys’ “God Only Knows.” Sean’s eyes teared up, and for a split second I forgot how much pain I was in. Waves crashed and seagulls cawed, and Gio, our little dog and ring bearer, found a cozy spot to sit in the sand next to my lace train. When I locked eyes with Sean, I saw all the pain, relief, happiness, and hope that had brought us here, and I felt it in my heart. As sappy and rom-com-y as it sounds, with an unspoken “we got this,” we really did become one in that moment. Because goddamn—neither of us had signed up for this life.

That night, as I danced with my husband—while leaning heavily on the sleek new rollator my mom had bought me as a wedding gift (which I promptly named Pearl)—and sang at the top of my lungs with my two sisters. I was in pain. I was disabled. I was in love. I was also frightened for what was to come, while grieving what I believed this moment should have looked like.

As happy and hopeful as I was for my future with Sean, this sense of grief followed me as I settled into married life. I found myself grappling with a pervasive sadness and feeling of loss mixed with confusion, denial, and disbelief. We weren’t driving off into the sunset like other newlyweds. Instead, we were sitting at home waiting for the arrival of my mobility service dog, and concern for my health was always top of mind. Had we missed out on the “fun years” before we’d even gotten started, and skipped straight to the part where our lives revolved around medical bills and fears about me falling in the shower? I loved Sean so much. But nothing about our union felt sexy or romantic anymore, and my heart was broken.

Like many of us, I am a self-proclaimed doer. I placed so much worth in my ability to get things done, and to get it done well, that grieving the significant loss of abilities that accompanied my diagnosis left me feeling helpless and less-than. I could not see or feel past my pain, and I knew by now that no treatment, medicine, or therapy would fix me. All I knew was that my body would never be able to perform the way it had.

How could the body that had been my home, that I had already helped to heal from my eating disorder, have turned on me? How could it be the cause of so much fresh suffering?

My body has betrayed me, I thought.

This is what I call Perceived Body Betrayal, the narrative that your body has somehow turned “against you.” It is the core driver of Body Grief—the sense of loss and mourning that comes with living in an ever-changing body—and what ultimately catapults all of us into a deep disconnect within our bodies and ourselves.

Body Trust

Perceived Body Betrayal is the feeling we get anytime our body changes in ways we are not able to control, does not recover fast enough from any setbacks, experiences pain, or is otherwise unable to perform on demand: that it is somehow against us. This is a maladaptive way of coping with our Body Grief; if what we are experiencing is our body’s fault, then we have something concrete to blame. And so we place ourselves at war with our bodies—when what is needed is compassion, grace, and a judgment-free zone in which to heal.

As with Body Grief, Perceived Body Betrayal stems from the societal message that our productivity, looks, and abilities are the primary measure of our worth, when in reality, all bodies of all colors, shapes, sizes, and genders hold equal value, in sickness and in health, and at every life stage. But all bodies are also destined to change, age, and experience different levels of productivity over the course of a person’s life. Refusing to accommodate these shifts erodes our innate Body Trust and throws us even deeper into Perceived Body Betrayal.

This is why I say Perceived Body Betrayal, not simply Body Betrayal. Many of us believe that our physical self is separate from our psychological and spiritual self. We often hear things like “Her body is failing her” or “His body gave up on him.” And while the underlying sentiment is well-meaning, I have a big problem with the subtext.

Our bodies are not separate from the rest of what makes us who we are, and they are not betraying us—ever. We just perceive they are, based on how we have been told they “should” perform. Our bodies will in fact do everything and anything to find a homeostasis, that is, to find balance, to function, and to maintain themselves. This is, in fact, always our bodies’ number one goal.

Sometimes the journey toward homeostasis is not pretty. In fact, it can be incredibly inconvenient, even painful. In my case, my body seeking homeostasis manifested as the swelling, rashes, failed fusions, pain, and body convulsions that were part of my Ehlers-Danlos syndrome diagnosis. For you, it may manifest as fatigue, burnout, anxiety, feeling like you can’t get enough sleep, increased appetite, nightmares, or racing thoughts.

But even when it hurts, our body is always doing what it can to protect us and keep us alive. As infants, before we have language, we have no option but to trust in the nonverbal cues our body sends us. Our body lets us know when to eat, when to sleep, when to poop, and when we need a hug—and at that age, that’s pretty much all we need to know! But as we mature and language takes over, we discover all sorts of ways to override our innate bodily needs. Rather than taking a nap when we’re tired, we caffeinate. Our stomach growls at us, and instead of taking time to sit down and eat a proper lunch, we have another coffee or grab a protein bar on the go. We feel uncomfortable in a social situation, so we chug another glass of wine. We disrupt our Body Trust on the daily, but our body never stops communicating with us. Speaking in both physical sensations and emotions, it signals to us when something needs our attention—be this a physical need or ailment that needs tending to, or when something it wants and needs is being presented to us and it wants us to say yes to it. Body Trust springs from leaning into this mind-body-spirit conversation.

All my debilitating symptoms, which required multiple surgeries to address, were ultimately ways that my body was trying to protect me. But because I had been programmed to believe that a healthy body was pain-free, worry-free, fully functioning, and always happy, I felt like my body was letting me down-when really it was simply fighting to find balance. Part of being with our Body Grief, and growing our capacity to stay in Body Trust, is remembering that our body is always on our side.

***

Prior to my clinical training as a therapist, I believed that I would not grieve until I experienced the loss of a loved one. But the reality is, to be human is to experience grief, because grief is intertwined with any and all experience of change. Whether it’s a new job, a move to a new city, a divorce from a longtime partner, or recovery from an addiction, regardless of the benefits these changes elicit, they can all induce grief. We grieve for the people we used to be, for the lives we used to live, and for the futures we thought we’d have.

Yet despite grief being our instinctive physical, emotional, and psychological response to loss, society doesn’t treat grief as a natural part of the human experience. Instead, it is something to be avoided, pathologized, and compartmentalized. Or, if we can afford it, we learn that grief is best dealt with behind closed therapist’s doors. But this only stifles our grieving response, which in turn makes us more prone to stress, deepens our trauma, and exacerbates our emotions.

This is what can make Body Grief so much more complicated, emotionally charged, and hard to navigate. There are very few dedicated forums in which we can openly grieve a death, let alone our own loss of bodily autonomy. Yet our Body Grief is just as big of a grievance as a death in the family; the loss creates just as deep of a wound.

Grief in all its forms wants and needs to be felt and expressed. This is what allows us to heal. With each difficult, messy emotion that is brought to the surface, acknowledgment is how we are able to tend to our wounds.

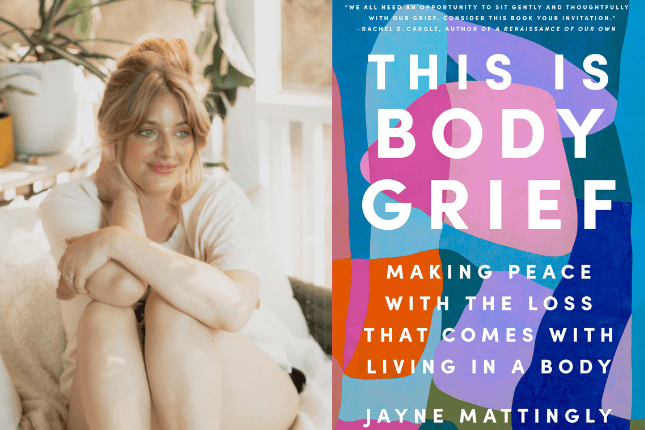

From THIS IS BODY GRIEF by Jayne Mattingly, published by Penguin Life, an imprint of Penguin Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC. Copyright © 2025 by Jayne Mattingly.

Jayne Mattingly

Jayne Mattingly is a crystal-loving, disabled baddie who knows that resilience and rest can coexist. With a master’s degree in Clinical Mental Health Counseling and a background as an eating disorder professional, she has spent her career helping others heal their relationships with their bodies. But her expertise isn’t just academic—it’s deeply personal. After enduring 19 brain and spine surgeries and a total hysterectomy in just six years, Jayne has lived the realities of Body Grief. Through her work, she challenges the toxic narrative that our bodies are broken, instead reminding us: our bodies have never been against us. Her mission is to help others find peace in their bodies, not in spite of their struggles, but because of them.