Early in my research on forgiveness, I asked my clinical colleagues to define what forgiveness means for them in their work.

“Forgiveness allows the opportunity for safety and trust to be reestablished in a relationship,” a marriage and family therapist told me. “I encourage all my clients to forgive.”

“Forgiveness is a virtue that follows the teachings of Jesus Christ,” said a Christian counselor. “Everyone should embrace forgiveness.”

“Forgiveness is a choice to let go of resentment,” said another psychologist. “It’s good for the forgiver, the forgiven, and the community. It’s a gift that benefits everyone.”

As this sampling of responses suggests, there isn’t a single, universally agreed upon definition of forgiveness, both in and outside of psychotherapy. However, I often see a common thread: forgiveness is almost always framed as a universally positive, necessary part of a healing journey; without it, true recovery remains elusive.

I question that. Just how necessary is forgiveness on the path to healing? Psychologist Sharon Lamb calls forgiveness “the porn of movies,” because the film industry’s depictions of forgiveness are just as inaccurate as the pornography industry’s depictions of sex. Films don’t really show what forgiveness from a survivor’s perspective actually looks like.

As a trauma therapist and survivor who’s spent almost two decades researching attachment trauma and forgiveness—and worked with hundreds of trauma survivors along the way—I’ve found that pushing forgiveness on our clients can be deeply triggering, wounding, and inhibit their recovery for years to come. I’ve heard many stories from clients who said therapists told them that forgiving their abusers was a requirement if they wanted to heal, that if they didn’t forgive the offender, they’d remain emotionally stuck and therapy would stall. Unsurprisingly, many of these clients ended therapy prematurely. Some told me they were so hurt by the experience that they didn’t return to therapy for years. Some never returned at all. They described their therapy experience with words like alienated, manipulated, and judged. It pains me to hear this, since I know these mistakes can be easily avoided.

To be clear, I’m not anti-forgiveness. But I do believe that, like any suggestion we make to clients, it should be used on a case-by-case basis. But how can you tell which clients may benefit from forgiveness and which ones may be hurt by it? What does it mean to forgive, anyway? And do trauma survivors really need to forgive their abusers in order to heal? As I began to explore these questions, I began to think back to the moment when my own trauma began.

First, My Parents Disappeared

I’m not sure when my father disappeared. I have few memories of him, although we lived in the same home for my entire childhood. I could see him, but he wasn’t there. He went to work, sat in the kitchen alone eating his meals, and retreated to the den or the porch to read the newspaper. He avoided his three children. Everyone viewed him as a kind, gentle, shy man, but trauma survivors know that those who are publicly perceived as friendly and charismatic are often the most vicious offenders.

My father had an affair and fathered a child when I was six. He was covertly paying a considerable amount of monthly child support, which I later learned was partially blackmail money intended to keep the mother and her family silent. No one in my family would discover the affair, the child, or where the money went until after he died. This revelation explained why our lower-middle-class lifestyle was quickly reduced to invisible poverty. At times, food was scarce, and as a child, I was responsible for fielding calls from bill collectors. We didn’t qualify for food stamps or free school lunches because my parents’ joint income was too high, and the blackmail payments were not documented. My father was financially abusive, as he controlled all the family’s money and never explained to my mother where it went. He also began controlling, manipulating, and isolating my mother. I believe that my father—whom I suspect suffered from undiagnosed and untreated depression and avoidant attachment—was destroyed by the strain of keeping his secret. He isolated himself for the remainder of his life. He lived in front of newspapers and TV screens, rarely speaking. He didn’t cook, clean, or care for his basic hygiene needs. He officially retreated into a hell of his own creation. That might have been tolerable since I never truly felt I had a father. Yet it became intolerable when he took my mother with him.

I was nine years old when my mother disappeared. This happened gradually due to an accumulation of adverse experiences, including a drastic and unexplained change in her financial security, working long hours, enduring spousal abuse, and the birth of her third child. I suspect she also suffered from undiagnosed and untreated depression and childhood complex trauma, which prevented her from coping, seeking help, and advocating for herself. The gardener who planted tulips in our front yard, the artist who sewed homemade Halloween costumes, and the loving mother who called her children by the pet names of Pretty Ditters, Mr. K., and Lambikins slowly slipped away. She stopped cooking and cleaning, and when she wasn’t working long hours to pay for a child she didn’t know existed, she locked herself in her bedroom. My father and extended family members told me that my mother was delicate and needed support.

“You need to be nice to your mother. She needs you,” said my grandmother.

“Promise me that you will look out for your mom,” my aunt implored.

“You need to behave so your mother doesn’t get too stressed,” my uncle insisted.

“Don’t upset your mother; you’ll kill her,” my father warned.

“Your mother matters; you don’t,” said my nine-year-old internal voice as it interpreted these messages during such a vital stage of development.

“Your mother matters; you don’t” became my motto. By the time I was eleven years old, most of my decisions were motivated by how they would impact my mother. If I got a B in math, would that upset mom? Would she get stressed if I told her I felt sick and needed to go to the doctor? Would she die if I misbehaved? There was no consideration for what I wanted or needed. I was consistently told to leave my mother alone, and I—the “good daughter”—did what I was told. I stopped knocking on her closed bedroom door, stopped telling her about my day, and left her alone. All I could do was watch as she slowly, steadily, and silently disappeared.

My childhood home became a physical manifestation of my disappearing family. My house was infested with colonies of cockroaches and spiders whose bites left welts. The floors were caked in dirt, the carpets were drenched in cat urine, and it was always cold because the windows leaked. I was isolated in that home and learned to create my own joy. I used kitchen knives to scrape the black grime from the floors, and I’d peer at the clean tan wood underneath in amazement. I fed the spiders who lived in the corners of my bedroom walls with ants and rollie pollies that I’d captured in the backyard. My favorite game was the “cockroach hunt.” My brother and I would creep into the kitchen at night and turn on all the lights at once. Colonies of cockroaches would then scurry away, and we’d see how many we could squash with our bare feet before they disappeared into the cracks in the walls and the rotted holes in the floor. We’d push and shove each other to sabotage the other’s success, yet we could never keep track of our kills, which caused heated late-night arguments. This is one of my happiest childhood memories.

From my point of view, my childhood was not unusual. The children who lived in clean houses with parents who were present, caring, and attentive were strange to me. Why did their parents want to know where their ten-year-old daughter, my friend, was at all times? Why did they cook her meals? How did they know her teacher’s name, her grades, and what she liked to do? Why did her parents talk to me? Why were they asking me about school and things that I liked? I assumed these girls were rich, as I attributed my living conditions and my parents’ disappearance to poverty. In fact, not having money was the excuse my parents used when others questioned their lifestyle. Yet, many children live in poverty and don’t experience emotional or physical neglect. The truth is that I was a victim of physical and emotional childhood neglect, and that neglect had become my way of life.

Then, I Disappeared

When you’re a child and your parents disappear, you have no choice but to join them. How does a child know they exist if their parents cannot see them? They don’t. How does a child acknowledge their value if their parents do not show them their value? They can’t. Without others, a child doesn’t truly exist.

Children need safe, healthy, capable adults to be their attachment figures. These adults serve as the foundation upon which children build other relationships. Imagine that you’re building a house upon a foundation that isn’t stable. Perhaps the concrete foundation wasn’t laid properly and, as a result, there are large cracks in it. You can build a house on this foundation, but it will need constant repairs and might collapse. This is what happens when you’re a child without an attachment figure. You’re constantly trying to build your house on a shaky foundation. To survive, I learned to disappear just like my parents. The clinical word for disappearing is dissociation, which means that you feel disconnected from yourself, others, and the world.

At 13 years old, I had limited emotional capabilities, as I couldn’t feel intense emotions. My brain and body could only tolerate mild-to-moderate short-term emotions. This meant that I rarely felt furious, fearful, or sad. Yet, I also didn’t feel much comfort, joy, or love. Dissociation is an automatic and unintentional survival response that impacts thoughts, emotions, and physical sensations. When I didn’t have enough food to eat, my body shut down, so I didn’t feel the hunger pangs. When I didn’t have warm clothes, my body went numb, so I didn’t feel the sting of the cold. When I was ill, I didn’t feel much pain at all. Dissociation helped to protect me, but it also left me feeling as if I didn’t physically or emotionally exist in the world; it made it difficult for me to know when I was seriously ill or injured, and it prevented me from connecting with others. When people physically touched me, I rarely felt it. I went through the motions of life mechanically, as if I were not fully alive, but not yet dead. I was neither truly present nor wholly absent; I was a ghost.

“Don’t you love your parents?” a high school classmate once asked me when they noticed I never mentioned my family.

“Of course I do. All kids love their parents,” I responded.

But I didn’t. As a teenager, I’d developed full-blown avoidant attachment. It’s challenging to explain attachment wounds to those who haven’t experienced them. This is why I don’t try to explain it. Instead, I show people a video clip of Dr. Edward Tronick’s “Still Face Experiment,” which explores the impact of childhood emotional neglect. The video shows a mother playing with her toddler daughter. They smile and laugh together until, suddenly, the mother stops engaging with her daughter and sits silently, motionlessly, with a blank stare on her face. The baby immediately knows that something isn’t right. Her mother has disappeared. The baby instinctively tries everything she can to get her mother to reengage. She smiles, points, reaches for her mother, screeches, and eventually cries with her arms and legs flailing at her sides. She has lost control of her body. Then, she looks away from her mother and disconnects. Perhaps she is trying to disappear, to follow her mother into whatever other world she entered. After two painful minutes, the mother reengages, and her daughter quickly smiles and reaches for her as they promptly repair the break in their connection. This cycle of connection–break–repair happens in all healthy relationships. However, when there’s no reengagement or repair, a child is left to figure out how to meet their emotional needs independently. I was that toddler, but my parents never reengaged, and all I could do was disappear. Some trauma survivors have nightmares of their offenders harming them or of the terrible events they experienced. My nightmares are of my parents’ still faces and vacant eyes and of that constant reminder: your mother matters; you don’t.

At age 33,I began intense trauma therapy. I participated in EMDR, attachment therapy, somatic experiencing, internal family systems therapy, and animal-assisted therapy; I engaged in support groups, took psychiatric medication, and embraced my realization that I was a trauma survivor. After five years, I’d made significant progress. I began to feel like I existed in the world and had value. I learned how to experience emotions and physical sensations. I rekindled my relationship with my older brother, began to build authentic friendships, and married a safe, loving partner. As a clinician, I continued my work with trauma survivors with renewed vitality, empathy, passion, and insight. I earned a reputation in Chicago as one of the top referrals for clients with severe complex trauma. Yet, there was one glaring obstacle in my recovery progress: forgiveness.

During therapy, I ceased all contact with my mother without any plans to reconcile. I did this for two reasons: First, she hadn’t changed much, and I didn’t see any evidence that she was capable of participating in the adult mother-daughter relationship that I needed. Second, I didn’t feel safe. She and my extended family were stuck in an intergenerational trauma dynamic, and I was determined to break the cycle. If I were to be in her life, I would be expected to act as her caregiver until her death, with no consideration given to how this would impact me. I knew that I needed estrangement. But did I need to forgive her to make more progress in my recovery? Or would forgiveness be harmful?

Before we consider this question, we need to start by recognizing that when forgiveness is forced, pressured, encouraged, or recommended by those in positions of perceived authority (mental health clinicians, religious leaders, authors, politicians, social media influencers, family, and friends, etc.), it can cause harm. Indeed, forgiveness can be one of the most significant obstacles in trauma recovery. Many believe that you will progress in therapy only if you forgive your offenders. Though usually well-intentioned, such a prescription can unintentionally cause harm when it fails to meet, or suppresses, your actual needs. Imposing forgiveness can sabotage trauma recovery by overriding or compromising your feelings of safety, by reinforcing damaging gender roles, by reinforcing societal inequalities, by hindering or attempting to repress your need to feel, express, and process negative feelings such as anger and rage, and by promoting shame and self-blame. Unfortunately, some people even intentionally use forgiveness as a weapon to harm, silence, or police you—or to in fact center and prioritize the interests of your offenders rather than those of survivors themselves—under the guise of moral virtue.

What is Elective Forgiveness?

How can we avoid harming trauma survivors with forgiveness? We can offer forgiveness not as a recovery requirement but as an elective. When a student attends college in America, they have several optional courses they must complete, called electives. A few of my college electives were creative writing, feminist literature, and badminton. I didn’t need to take a feminist literature class to earn a degree in psychology, but I found it to be a helpful addition to my academic course of study. Many students wouldn’t find a feminist literature course helpful and are free to choose a different elective.

What happens when we consider forgiveness as an elective? You may choose to forgive, you may choose not to, and you may not initially choose to forgive yet find that you unintentionally experience organic forgiveness. You may forgive on your own terms in your own time, while others may experience various levels of forgiveness (which may fluctuate over time). You might choose to withhold, resist, or forgo forgiveness. You might not be capable of authentic forgiveness no matter how hard you try and therefore cannot make a choice. Elective forgiveness can meet you where you are at in each moment regarding your capabilities, as it creates an environment where forgiveness is no longer an obligatory component of trauma recovery. When I permitted myself to consider forgiveness as an elective, I experienced forgiveness for some of my offenders and not for others, and I continued to progress in my recovery.

Forgiveness should never be forced, pressured, encouraged, or recommended for trauma survivors in recovery. Elective forgiveness can take the experience of forgiveness off the recovery table unless you need it to be on your table or it organically appears. In contrast, forgiveness should never be discouraged, shunned, or sabotaged in recovery when it does not negatively impact your safety. Forgiveness should be viewed as an elective component of trauma recovery. You should have the agency to explore, discover, embrace, ignore, oppose, or withhold forgiveness throughout your recovery. This neutral approach to forgiveness can be helpful to you and anyone involved in their recovery journeys, such as mental health clinicians, family, friends, life coaches, religious leaders, and community members.

In case I haven’t been clear enough already: I’m not antiforgiveness. My thesis isn’t that forgiveness is always wrong or clinically counterproductive; indeed, many trauma survivors benefit from forgiving their offenders. My position, rather, is that forgiveness is not universally necessary for trauma recovery and that not only are suppositions to the contrary poorly supported by actual empirical research, but they’re also problematic for both ethical and clinical reasons. To question forgiveness feels like an act of all-out rebellion.

As philosopher Jeffrie Murphy would say, I’m “bucking a trendy and almost messianic sentimental movement that sees forgiveness as a nearly universal panacea for all mental, moral, and spiritual ills.”

If you’re a trauma survivor, you may choose to forgive or not to forgive, or you might not be able to forgive at all. I hope that your journey is based on your specific recovery needs. If you’re a mental health clinician, you’ll need to determine how you perceive forgiveness in trauma recovery. I hope your clinician integration is based on the specific needs of your clients and not your own. Forgiveness is not a panacea.

Decades after my own trauma, I’ve allowed myself to take forgiveness off the table as far as my recovery is concerned—but I’m also leaving space for it in the future, if I find a need for it.

***

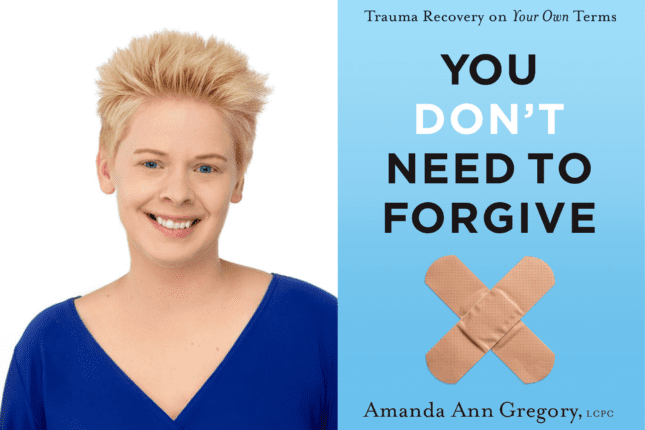

Excerpted from You Don’t Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery on Your Own Terms, by Amanda Gregory.

Amanda Ann Gregory

Amanda Ann Gregory, LCPC is a trauma psychotherapist renowned for her work in complex trauma recovery, notably as the author of You Don’t Need to Forgive: Trauma Recovery on Your Own Terms. With a keen focus on the specific needs of trauma survivors, Gregory’s expertise spans over 18 years in clinical practice. She has been featured in The New York Times, The Guardian, National Geographic, and Newsweek and published in Psychology Today, Psychotherapy Networker, and on Psychotheray.net. Find out more at www.amandaanngregory.com.