The session was supposed to be a consultation between two middle-aged sisters—my client, Annie, and her sister, Carol—about sharing their multigenerational summer house on Nantucket Island. They’d never been particularly close, but their relationship had soured in the last few years, as they’d been struggling to navigate the scheduling, maintenance, and financial management of the house. The summer before, in fact, they’d had a huge blowup over which family would get to use it on July 4th weekend—after which they didn’t speak for six months.

Seated in my office, they started off, in a polite but guarded way, talking about certain dilemmas they hadn’t been able to resolve, like whether to replace the storm windows, given that they disagreed about its necessity. Rapidly, however, the conversation degraded into a heated debate about who was at fault for the July 4th mess. Then it veered into even more complicated territory.

“Of course you’d say it was just an innocent misunderstanding,” Carol scoffed. “God forbid you admit to being selfish. You were always such a goody two-shoes. No wonder Daddy liked you better!”

Annie stiffened and responded with a thin smile. “That’s not true at all. I just didn’t fight with him all the time. Besides, he might’ve been nicer to you if you weren’t always getting between him and Mom and taking her side. It made him lose his temper.”

“Hold on, you two,” I jumped in. “One of the things that can make relationships between adult siblings so fragile is that while siblings may have lived under the same roof as children, they may have had totally different childhoods—and a limited understanding of what the other was going through because, after all, they were just kids at time.”

Regardless of their presenting problem, adult siblings often bring with them a dense and complicated history that’s never been fully addressed. I’ve worked with many adult-sibling combinations over my years in practice—whether it’s been two, three, or as many as four of them at a time—and at some point, no matter what age they are, they slip back into old childhood roles and relationships.

Annie and Carol were no different. They listened to me politely, but the room was rife with tension, and I could easily sense the 8- and 10-year-old sisters the way they used to be.

I’ve often been drawn into working with siblings at the request of one of my clients. This can be tricky. If one sibling is your ongoing client, it may be best to refer this kind of consultation out to another therapist. However, if both siblings really want to do the work with you, you can do well to keep a few factors in mind.

First, make sure your client is prepared to see you in a neutral role, as opposed to the advocate you are as the individual therapist. This is often much harder than your client expects, so reassure her that listening attentively to the sibling’s point of view isn’t the same as agreeing with it.

Second, get permission to have a private and confidential session with the other sibling before the joint session. Careful joining is critical. If the other sibling has a therapist, see if you can speak with the therapist directly. It just takes a phone call to get a sense of their concerns and goals for their client about the sibling consultation.

Third, it’s essential to clarify what the siblings’ goals are at the beginning of their individual sessions, as well as at the start of their joint work. It’s fine for them to have different goals, as long as they’re clearly stated.

The heart of many siblings’ conflicts is not so much the presenting problems, but their leftover feelings from dramatically differing experiences of growing up and their wish to have their individual truths validated by their sibling. I usually have to remind siblings that it’s possible to have two truths that are different.

Sometimes your client may want to do deep-healing work with an estranged sibling, wishing to make amends, improve the relationship, work through a longstanding conflict, or have the sibling offer some long overdue apology. In these instances, your client should know that they may need to do most of the work themselves, rather than expect full reciprocity. This is especially true if your client is in the pursuer role and the other sibling sees themselves as the aggrieved party.

If your client is considering making amends, you’ll need to make sure they’re prepared to ask if the sibling wants amends and that they’re prepared to take no for an answer. Sometimes the best possible outcome is just for them to feel like they made an effort. If the sibling can’t reciprocate, then letting go, rather than pursuing, is an appropriate approach.

Often the siblings may need to accept that it’s possible to improve their relationship without agreeing about issues or becoming friends. In Annie and Carol’s case, I knew Annie was hoping for a deeper level of rapprochement, but Carol had asked for more of a mediation than an attempt at reconciliation. They did some respectful work together, buried the hatchet as best they could, and agreed to improve how they share family get-togethers at the house; however, Carol was clear that she wanted to stop there. “It seems like there’s just too much water under the bridge,” she said.

“Sadly, this may be one time I actually agree with you,” Annie said with a rueful smile.

Some years after I finished my work with Annie, I was surprised to get this note from her: Guess what? Carol and I are hiking Hadrian’s Wall in Scotland this summer. Just us. Our great-grandparents were from there, and we’re going to visit our roots. We’ve been getting along well for the last few years. Can you believe it? Thought you ought to know.

I don’t know exactly what happened to bring them together. Sometimes it’s as simple as giving the impact of the sessions time to be realized. Sometimes helping siblings acknowledge together that they aren’t ready to work on deeper healing is reparative in its own right, because they’re being collaborative with each other in making that choice. And often the old systemic intervention of helping the pursuer stop pursuing helps the distancer stop distancing, just slowly over time.

Part of the miracle of therapy is that we may not know what catalytic events lead to positive change. However their reconnection happened, though, reading Annie’s note made my heart smile for those two hurting young girls from long ago.

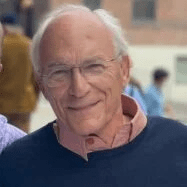

David Treadway

David Treadway, PhD, has been a therapist and trainer for 40 years. The winner of the Rich Simon Award for Outstanding Writing, his fifth and latest book is Treating Couples Well: A Practical Guide to Collaborative Couple Therapy. Contact: dctcrow@aol.com.