An anthropologist’s daughter, I came of age on Upolu, Samoa, living by a turquoise lagoon in an indigenous village and kinship group that formally adopted my family. Our beloved community thrived on the bounty of seafood from the reefs, and crops like taro and coconuts. We bathed in freshwater springs, our nights lit by oil lamps and moonlight.

I finished high school in Australia, then journeyed in a dugout canoe up the Rejang river, through the pristine jungles of Sarawak. In my early 30’s, I learned to dive among the teeming life of the Great Barrier Reef’s phantasmagorical underwater universe.

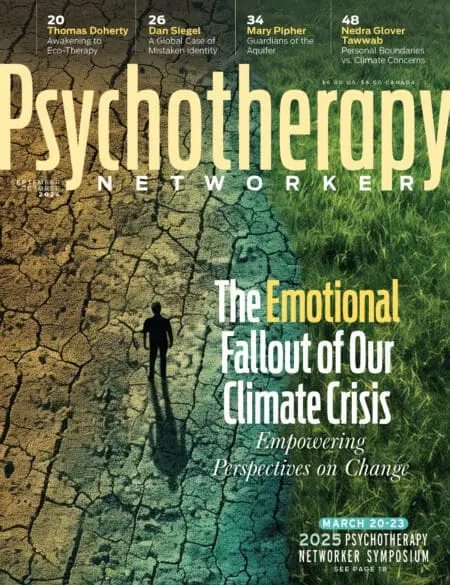

My early life was intertwined with exquisite natural beauty, yet I’m of the generation that’s witnessing swaths of jungle turn into logged-out wasteland. The reef paradises are fading out. Facing the ever-growing risk of tsunamis, my Samoan village moved inland along a paved road. With the ocean’s rise, the island beaches I love are beginning to swirl away.

Fifteen years ago, I wrote an email to everyone I knew, saying that based on predictions for climate and environmental degradation, we must drop everything and step up to help the planet. Embarrassed about being overly-dramatic, it remained in my draft box. For years, I’ve cried over news of environmental losses. The trouble is, my brain and yours are designed to respond to more immediate dangers. For many of us, the environmental “slowpocalypse” is unfolding gradually and distantly. This keeps the truth of our impacts at bay.

Even so, I’m hearing alarmed narratives from clients in my practice, especially since the UN released a report giving humans 20 years to radically change the way we live before temperatures rise irrevocably, exacerbating mass extinctions. A client in her 60s said, “My daughters don’t have confidence that our world will last. What do I say to that?”

In Northern California, where I work, the 2018 fires choked us all with toxic smoke. When bickering eight-year-old twins arrived for family therapy wearing protective masks, it so flummoxed me that, despite decades of experience, all we did was joke about the masks. After that, I realized that by shying away from connecting fears of intensified fires with human-caused climate changes, I was complicit with understandable avoidance and inaction.

My middle-class therapist’s lifestyle is tied into an economy of resource extraction that disproportionately impacts others around the planet, compared to the healthy sustainable economy of my Samoan village. At the same time, I belong to a group of professionals who have skills and resources to address this eco-emergency. It seems deeply ethical in such times, that we adapt to these priorities.

But I wonder, will we in the therapy world take action to prevent mental health morasses caused by environmental crises? Or, having fallen prey to the isolating psychology of individualism, will we find ourselves checking diagnostic boxes like Pre-or Post-Traumatic Climate Disaster Disorder and end up being paid to simply assuage eco-anxiety, eco-depression, and eco-trauma?

We have an opportunity right now to find a pathway between denial and catastrophizing; and support everyone to step up and make a difference. Moving forward, I vow to step out of the “business as usual” frame, inquire into my clients’ relationship to climate change, help them face aspects of denial, eco-anxiety and grief, and walk alongside them on pathways of possibility and engagement in this era.

“Not Enough People Care”

My client Lara, 29, is a teacher who saw Al Gore’s climate change documentary, An Inconvenient Truth, when she was eleven.

“My family discussed it, but there was no room for feelings,” she says. “Looking back, my sense of safety shattered. It made other bad things, like when mom got cancer, feel worse. Life felt really uncertain. I got angry and opinionated and tried to convince people to change. I avoided meat and rode my bike everywhere. But underneath, I felt out of control. At 19, I started shooting up drugs. As the climate got less reversible, I got more depressed, even though I managed to get clean in my early 20s. I think I was in crisis about the very idea of recovery, not just my own but the planet’s. I just kept thinking, not enough people care. You know, I’m biking and everyone else is driving to class. Everyone.”

**********************************************************************************

Are your clients trapped in a cycle of anxious thinking? Here’s a FREE printable worksheet you can use today to help them examine and work through it.

**********************************************************************************

Thinking about clients like Lara, who was deeply upset by environmental issues, I’ve realized that therapists can collaborate and encourage a proactive relationship with climate change if we face this crisis/opportunity ourselves. I’m inspired by environmental activist Joanna Macy’s project, The Work that Reconnects Network, which helps communities experience their deep emotions about the natural world and respond to its needs. She’s helped me soften instead of avoiding or despairing when encountering dystopian stories. I worked with an indigenous psychosocial response team after the 2009 tsunami in Samoa. As I witnessed from survivors there who were collectively healing and rebuilding, energized engagement is an antidote to overwhelm. For non-dominant populations, such as those dealing with Katrina and Flint, turning to resources like extended kin networks and church communities is essential.

When my clients say they feel helpless to respond, like they’re just a drop in an endless ocean, I pass on what eco-therapist Ariana Candell reminded me of on a walk we took together in nature, that the ocean is made of drops. To navigate “end of days” overwhelm, we can share emergent, liberating stories. I told Lara about environmentalist Paul Hawken’s book, Blessed Unrest, which describes those around the world working for environmental and social justice as contributing to the largest movement in human history. It reminded us both that we’re in the company of millions of caring, ingenious people.

As our work progressed, I asked Lara how her relationship to climate change has been evolving. She told me she’s put an end to “Debbie Downer” conversations.

“I’m into having my feelings,” she says, “But I’m also asking, what’s my responsibility as a young white woman? I passionately want to help build community that’s inspired to engage with these issues.”

I like her hit on it. Lara now has what eco-psychologist Thomas Doherty calls a positive “environmental identity.” By orienting toward their innate senses of caring and resourcefulness, we can encourage our clients to be revitalized and empowered through action.

Just imagine what it would mean if even a portion those whose lives we touch developed their eco-identity with a cause—habitats, sustainable food production, reforestation, renewable energy design, the intersection of social justice and environment, or a green economy?

We humans are not separate from nature, we are nature. Leaving behind the sense of grim, pressured responsibility that can accompany our climate crises, how extraordinary if we, with our clients, become part of the collective who are creating a counter-tsunami of responsive love for our exquisitely beautiful earth.

Photo © Sarayut Thaneerat/Dreamstime.com

Jennifer Freeman

Jennifer Freeman is a psychotherapist, author, and international presenter, based in Berkeley, California.