Editor’s Note: We were on our way to print with this issue when George Floyd was killed at the hands of police and the country surged in collective pain and protest. This article is excerpted from “The View from Black America” (November/December 2015, America’s Conversation about Race).

I’ve spent the last four decades of my life working with young Black people who feel trapped in a wall-less prison, who live their lives hidden in the shadows of invisibility as far as white society is concerned. They know all too well that their daily experience—whether it’s going to underfunded schools, absorbing constant microaggressions, or being the victims of discrimination and police brutality—doesn’t matter unless it interferes with or disrupts the lives of the white mainstream. While deeply rooted in the racial fabric of our country’s history, life inside the wall-less prison remains a mostly untold story.

Black kids know perfectly well how they’re perceived by white society: they’re threatening thugs and future criminals who need to be contained by any means necessary. Isn’t this the prevailing sentiment that undergirds the shooting of countless numbers of unarmed Black men by law enforcement? Whether in a car or walking, running toward or away from the police, exercising or playing with a toy gun, the narrative is always the same: they were dangerous and we feared for our lives.

At an early age, I’d learned that it could even be dangerous to use your hands around white people. When my friend Julius and I would go shopping with our parents, we were sternly told, “Now, be sure to keep your hands in your pockets while we’re in the store. Do you understand me?” Writing this now brings tears to my eyes. Keeping our hands in our pockets was an accommodation that we had to make for white people because our parents worried that we’d be presumed criminals—even as five-year-olds. Julius, now a respected physician, recently mentioned that he still finds himself jamming his hands into his pockets when walking through a department store.

This is what Black parents refer to when they mention “having the talk” with their children. “The talk” is a toolkit for racial survival designed to remind Black children that they’re living in a white world, where they’ll often be prejudged and presumed guilty until proven innocent—and the latter is no easy task.

My great-grandmother once implored me, “Kenny, please do something with your life. Make a difference in the world, even if it’s a small one. Too many Black people have died for us just to have you squander your precious life.” These words helped shape how I practice as a therapist.

My first full-time permanent position as a clinician was in an outpatient mental health facility in Brooklyn, where I served as director of group and family treatment. My clients were mostly from low-income African American and Latinx families. Their referral sheets typically showed presenting problems similar to what we’d expect to find in any behavioral-health treatment center: anxiety and other affective disorders, psychoses, and myriad child-centered family dysfunctions, all compounded by trauma.

In treatment, however, clients routinely discussed problems that I was never taught to address in my graduate training or the primarily white university-based clinics where I’d worked. These problems centered on social issues that seemed beyond the reach of the psychological solutions that constituted our preferred treatment protocol. Efforts to uncover the roots of depression, rage, or other serious mental-health issues repeatedly focused on clients’ biology, psychology, and family-of-origin experiences, but almost never on their ecology and the impact of their environment.

I was trying to be what I’d learned a good white clinician should be. Luis knew this and had done me an enormous service by calling me on it.

I’d never treated clients of color before accepting this position, but their experiences felt familiar. For the first time as a practicing clinician, I could breathe freely. Gone was the anxiety about greeting clients in the waiting room and the sudden paralysis they’d exhibit when discovering that their therapist wasn’t white. I relished being able to practice in a context where my race didn’t seem to matter. I felt that this job was a godsend. It’s what I believed I was called to do.

But I soon learned that my starry-eyed dream and the reality didn’t quite match. Early on, I felt a barrier to connecting with my clients that I found hard to name. Eventually, my clients and colleagues began to name it for me. The first was my Latinx client Luis, who announced one day at an awkward juncture in a session, “I don’t really get you, man. You look Black, but everything else about you tells me you’re white. I really can’t trust someone like you, who has the complexion but not the connection. I’m not technically Black, but I feel blacker than you.” In gaining my professional credentials, had I lost my soul as a Black person?

Dr. Stevenson, the white chief psychologist and my immediate supervisor, had welcomed me with high expectations. He wanted to develop a strong family therapy program and repeatedly emphasized the importance of rooting it in a solid clinical foundation, nothing way out or radical. Whenever I brought up the possibility of addressing issues of race in therapy, he either saw it as a distraction from “real” clinical issues or intimated that I was allowing my personal views to obscure good therapeutic judgment.

It all came to a head one day when he pulled me aside and said, “Dr. Hardy, I’m going to remind you again, since you seem to suffer from some short-term memory, that we’re a psychiatric outpatient clinic, not the NAACP or Amnesty International. I suggest you take time during this forthcoming weekend to decide if this is the place for you. We’re a mental health facility. Do you understand?”

I was stunned and infuriated by his sarcasm and condescension. After sitting in silence for a few minutes, overcome with emotion that I was trying desperately to ward off, I turned to him and began to angrily lecture him in return. “Who do you think you are?” I spat. “Do you think you can talk to me any way you want because you’re white? I know you don’t want to acknowledge race, but for me this is racial. I do not wish to be in a relationship with you or anyone else where I’m disrespected, talked down to, and treated as if I’m nonhuman. I’m sick of this!”

After listening with a look of cool disdain on his face, he calmly said, “Dr. Hardy you’re quite an interesting character. Once again you’re inappropriately introducing race into our discussion. I’ve had enough of this. Our meeting is over.”

When I returned to work the next Monday, the executive director, Stevenson’s boss, asked me to resign. For months afterward, I was haunted by what had happened.

It took me a little over a year to find another clinical job, but that gave me an opportunity to sort out what had happened. I was too white for the Black people I worked with, and too Black for my colleagues like Stevenson. I’d tried to play the game of belonging and fitting in, but instead I’d become an unwelcomed foreigner without a home.

Slowly, out of my endless self-reflection, came a kind of personal epiphany. I began to see that what was missing from my therapy with clients like Luis was a full embrace of who I was as a Black person. I was so worried about fitting in that I was constantly adjusting who I was to fit the situation. I was playing the role of the stoically detached professional, trying to be as impenetrable as possible.

I was trying to be what I’d learned a good white clinician should be. Luis knew this and had done me an enormous service by calling me on it. In a strange way, it was my jailbreak moment with Stevenson that allowed the parts of me that had anxiously hidden inside my personal wall-less prison to break out.

I found a nonclinical job at a youth-service program in an impoverished Black community with a Black staff, and it was an entirely different experience. It gave me an opportunity to reconnect every day with other Black people and experience a deeper, fuller sense of home. I felt part of a community where it was okay to give voice to the role of race in our clients’ day-to-day struggles.

Today, I spend much of my time working as a consultant on improving racial relationships within large healthcare and social service systems. Increasingly, my work has become centered on issues like the anatomy of racial rage, learned voicelessness, and an array of other invisible wounds of racial oppression. At the same time, I continue to maintain a practice where I see how easy it is to lose perspective on the social issues that shape our clients’ lives. To address the powerful role oppression played in my clients’ lives, I’ve come to see my mission as being not only a therapeutic healer doling out help in one-hour appointment slots, but also an activist and a bridge-builder.

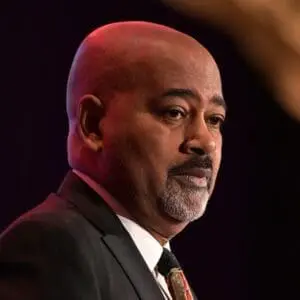

PHOTO © GETTYIMAGES/MARKMAKELA

Kenneth V. Hardy

Kenneth V. Hardy, PhD, is President of the Eikenberg Academy for Social Justice and Clinical and Organizational Consultant for the Eikenberg Institute for Relationships in NYC, as well as a former Professor of Family Therapy at both Syracuse University, NY, and Drexel University, PA. He’s also the author of Racial Trauma: Clinical Strategies and Techniques for Healing Invisible Wounds, and The Enduring, Invisible, and Ubiquitous Centrality of Whiteness, and editor of On Becoming a Racially Sensitive Therapist: Race and Clinical Practice.